728x90

Carving a two-mile-long canyon through the

heart of Southern California might seem like apostasy in this age of

low-impact land use. But the Orange County Great Park is no ordinary

place. To build this winding canyon, excavating machines will move over

five million cubic yards of earth to create a sluice of space up to 60

feet deep, with selective cuts framing views of the Santa Ana

Mountains, all culminating in a new, 26-acre lake.

All images courtesy Great Park Design Studio

“The

canyon is at once obvious and also unexpected,” said Ken Smith,

principal of Ken Smith Landscape Architect, which won a competition in

2006 to become master designer for the 1,347-acre park. “The whole

natural landscape in Southern California is composed of canyons. But

this site is so flat and barren, the idea to create a feature of this

scale is not something people had really thought of.” Moreover, the

canyon proved a logical design move because it could be built fairly

easily in a region where grading golf fairways is second nature to

contractors. Besides restoring fast-depleting natural habitat, the

space is so large that it will create its own microclimate: a cool

respite for park visitors. As Smith observed, “It’s a big canvas.”

At almost twice the size of New York’s Central Park, the Great Park will be the core of a 4,700-acre community built virtually from scratch on the site of the El Toro Marine Corps Air Station in Irvine, California. As the heart of this new chunk of Orange County, the park represents a complex and interlocking model of sustainable development for Southern California and beyond, where once-open vistas have been boxed in by suburban growth. Taking a macro-scale approach, the park will restore critical native plant and animal communities. By integrating with the densifying neighborhoods around it, the park promotes a walkable lifestyle in the land of sprawl. And it brings together diverse user groups to create for the county a sorely needed cultural heart.

At almost twice the size of New York’s Central Park, the Great Park will be the core of a 4,700-acre community built virtually from scratch on the site of the El Toro Marine Corps Air Station in Irvine, California. As the heart of this new chunk of Orange County, the park represents a complex and interlocking model of sustainable development for Southern California and beyond, where once-open vistas have been boxed in by suburban growth. Taking a macro-scale approach, the park will restore critical native plant and animal communities. By integrating with the densifying neighborhoods around it, the park promotes a walkable lifestyle in the land of sprawl. And it brings together diverse user groups to create for the county a sorely needed cultural heart.

The

Great Park is an unusual partnership between the federal government, a

private developer, and the city of Irvine. Following the air base’s

closure in 1999, a voter initiative called for a park and nature

preserve on the site. The entire property was purchased at auction by

Miami-based developer Lennar Corporation, which transferred the Great

Park parcel to the city of Irvine. The park is operated by a nonprofit

corporation, whose directors consist largely of elected officials from

the city of Irvine, along with other local stakeholders.

Now in the schematic design phase, the park’s parameters were laid out by Irvine planners, who set it upon a bare expanse of earth and concrete. “It came with quite a bit of the brownfields as well,” Smith said. Those include a chemical plume reaching 200 feet down into groundwater, which the U.S. Navy is obliged to clean up. As part of its development agreement, Lennar has put $400 million toward the park and related infrastructure, while another share of the park’s estimated $1.5 billion budget is expected to come from tax-increment bonding, as adjacent property values rise.

From the outset, Smith and his partners—including Los Angeles– based landscape architect Mia Lehrer and Enrique Norten of TEN Arquitectos—conceived of the park as a showplace of sustainability. The site’s environmental backbone is a series of ecological restorations that will renew the region’s vanishing natural diversity. Among the first sections to be built is a two-mile-long wildlife corridor: a missing link in a stretch of land reserves said to be the largest interconnected open space system in the country.

“It’s rare that an ecologist is asked to sit at the table when the basic ground plan is being determined,” said Steven Handel, president of New Jersey–based Green Shield Ecology, who has been part of the design team from the outset. “A lot of the basic plan grew out of ecological principles, not just design decisions.” The wildlife zone has been detailed to create habitats for birds, bobcats, and even a pack of coyotes, down to supplying rocks so the lizards have a place to warm up in the morning. “I’m rebuilding a whole world out of nothing,” Handel said.

Now in the schematic design phase, the park’s parameters were laid out by Irvine planners, who set it upon a bare expanse of earth and concrete. “It came with quite a bit of the brownfields as well,” Smith said. Those include a chemical plume reaching 200 feet down into groundwater, which the U.S. Navy is obliged to clean up. As part of its development agreement, Lennar has put $400 million toward the park and related infrastructure, while another share of the park’s estimated $1.5 billion budget is expected to come from tax-increment bonding, as adjacent property values rise.

From the outset, Smith and his partners—including Los Angeles– based landscape architect Mia Lehrer and Enrique Norten of TEN Arquitectos—conceived of the park as a showplace of sustainability. The site’s environmental backbone is a series of ecological restorations that will renew the region’s vanishing natural diversity. Among the first sections to be built is a two-mile-long wildlife corridor: a missing link in a stretch of land reserves said to be the largest interconnected open space system in the country.

“It’s rare that an ecologist is asked to sit at the table when the basic ground plan is being determined,” said Steven Handel, president of New Jersey–based Green Shield Ecology, who has been part of the design team from the outset. “A lot of the basic plan grew out of ecological principles, not just design decisions.” The wildlife zone has been detailed to create habitats for birds, bobcats, and even a pack of coyotes, down to supplying rocks so the lizards have a place to warm up in the morning. “I’m rebuilding a whole world out of nothing,” Handel said.

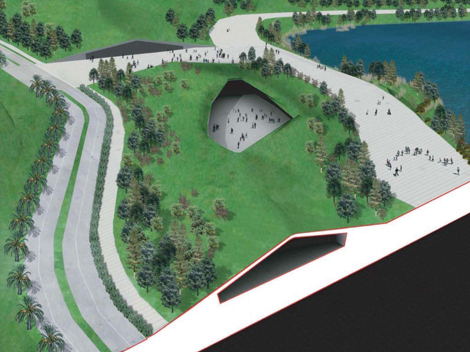

Other

worlds will be built here, too. “The most visited sites for people who

live in Orange County are the shopping centers and the beaches,” said

Lehrer, senior partner at Mia Lehrer+Associates. “There’s a real void

in terms of a cultural center.” Institutions will cluster in the park’s

“cultural terrace,” where buildings are being designed by TEN

Arquitectos as earth-bermed structures cut into the canyon. Park

leaders are evaluating a variety of programs—an amphitheater, museums,

a public library—many of which are expected to be public-private

partnerships. For example, the park has offered land at no cost to the

National Archives, which hopes to build a regional facility on the

site. The structure would be designed in cooperation with the Great

Park design studio, and funded through both public and private support.

Sustainability factors into the park’s connection with its surrounding community, which Lennar has envisioned as more than just sprawl. The planned residential, retail, and commercial areas include a 378-acre transit-oriented development, as well as a “lifelong learning” district designed as a dense, academic neighborhood with a core of college campuses extending to the Great Park’s sports facilities. The design team has closely worked with the developer on “edge integration” issues, such as reinforcing park spaces along Lennar’s campus main street.

In another eco-conscious approach, parking lots will be placed at the perimeter, with a system of shuttles to all major facilities—a strategy adopted by none other than Disneyland. (“That’s one of the rare forms of public transportation that many Southern Californians use,” Smith said.) The shuttles will link to a streetcar system with stops in the park, to be constructed as part of Irvine’s planned urban rail network.

Sustainability factors into the park’s connection with its surrounding community, which Lennar has envisioned as more than just sprawl. The planned residential, retail, and commercial areas include a 378-acre transit-oriented development, as well as a “lifelong learning” district designed as a dense, academic neighborhood with a core of college campuses extending to the Great Park’s sports facilities. The design team has closely worked with the developer on “edge integration” issues, such as reinforcing park spaces along Lennar’s campus main street.

In another eco-conscious approach, parking lots will be placed at the perimeter, with a system of shuttles to all major facilities—a strategy adopted by none other than Disneyland. (“That’s one of the rare forms of public transportation that many Southern Californians use,” Smith said.) The shuttles will link to a streetcar system with stops in the park, to be constructed as part of Irvine’s planned urban rail network.

The

most critical ingredient for any park is a strong constituency. To that

end, designers have rolled out the 27-acre Preview Park, anchored by an

orange helium balloon that has taken tens of thousands of visitors

aloft on free flights. It has also hosted concerts, art exhibits, and

kite-flying events around picnic areas and a five-acre meadow. Indeed,

aggressive public outreach has drawn an outpouring from user groups

eager to become a part of this grand experiment, from fly-fishing

enthusiasts to model-airplane buffs. Almost 2,000 county residents have

weighed in on their favorites among dozens of potential park programs.

It remains to be seen whether one park—however ambitious—can reinvent the Orange County suburbs. “You ask yourself whether the next phase of development for this area will come along with higher density,” Lehrer said. “Do people appreciate the opportunities and potential sacrifices of not having their own palace?”

Across America, smarter growth is increasingly a question not of if but when. As planners complete portions of the Great Park over the next five years—a full build-out is expected to take a decade—they will knit together a sustainable fabric of landscape and architecture, nature and culture. As a new Central Park for a much different time and place, it’s the best argument yet for Orange County’s greater, greener good. Jeff Byles

It remains to be seen whether one park—however ambitious—can reinvent the Orange County suburbs. “You ask yourself whether the next phase of development for this area will come along with higher density,” Lehrer said. “Do people appreciate the opportunities and potential sacrifices of not having their own palace?”

Across America, smarter growth is increasingly a question not of if but when. As planners complete portions of the Great Park over the next five years—a full build-out is expected to take a decade—they will knit together a sustainable fabric of landscape and architecture, nature and culture. As a new Central Park for a much different time and place, it’s the best argument yet for Orange County’s greater, greener good. Jeff Byles

그리드형

'Landscape' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [ Consortium Daoust Lestage + Williams Asselin Ackaoui + Option aménagement ] Promenade Samuel-de Champlain (0) | 2009.10.01 |

|---|---|

| [ Arteks Arquitectura ] “Pinar del Perruquet” Park (0) | 2009.10.01 |

| [ PLOT ] Copenhagen Harbour Bath (0) | 2009.09.30 |

| [ Matsys Designs ] Sietch Nevada (0) | 2009.09.26 |

| [ Bjørbekk & Lindheim ] Nansen Park (0) | 2009.09.07 |